Research: An Exploration of Mental Health and Psychosocial Supports Available to Refugees and Asylum Seekers Globally

ICHAS Student Stefanie Jaeger Liston recently conducted research on an exploration of mental health and psychosocial supports available to refugees and asylum seekers globally. Below is a summary of her research and some of the key findings and recommendations.

“We don’t heal in isolation, but in community.”

—S. Kelley Harrell, Gift of the Dreamtime: Awakening to the divinity of trauma, Reader’s Companion (2014).

Background to Mental Health and Psychosocial Supports Available to Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Research has shown that migration has a direct impact on refugees’ mental health, thus refugees and asylum seekers often present with heightened mental health needs. Global conflicts and humanitarian crisis are ongoing and the number of refugees in need of psycho-social support has risen dramatically and will continue to do so. This presents a challenge for existing mental health services. Refugees are a particularly vulnerable group and face additional barriers to accessing basic support services. Yet they are advised to access mental health services through the public health system, which is already challenged by high demand and a lack of resources. Consequently, the availability, accessibility, and suitability of mental health supports for asylum seekers continues to be inappropriate and unsatisfactory. Innovative, effective, and scalable models for refugee mental health care are needed to address the rising need. This study aims to examine evidence of mental health and psychosocial supports available to refugees and asylum seekers globally. It is hoped that the learning will inform current practice in Ireland.

What is Psycho-Social Support?

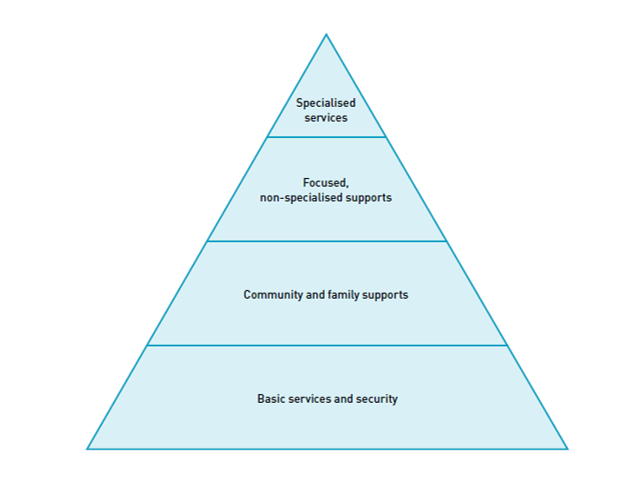

Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) describes any type of supports, locally or externally, that aims to promote and protect psychosocial well-being and/or treat and prevent mental disorders (IASC, 2007). As illustrated in the triangle below, an MHPSS response includes addressing basic physical needs such as food, shelter, and health care as well as community and family support interventions including educational opportunities, social networks, and parenting programmes. The third layer in the MHPSS pyramid shows non-specialised supports focusing on individual, family, or group interventions. This may include low-intensity psychological interventions, mind-body approaches such as grounding and breathing exercises, structured play for children, and sports and art activities. As highlighted, only a small percentage of the overall support-seeking population will need psychological or psychiatric support and/or pharmacological treatment (IASC, 2007:13).

Key Findings & Recommendations

Key Findings & Recommendations

Most psychotherapeutic interventions focused on treating individuals with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). However, the prevalence of PTSD among refugees, although higher than in the general population, varies greatly. Not everyone experiencing trauma will develop PTSD. Equally, not everyone with psychological distress needs psychological intervention. Authors agree that other mental health disorders have been largely neglected and that there is a need for a more nuanced approach to refugee mental health care.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Narrative Exposure Therapy, and Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) were the most frequently used interventions and have shown satisfactory results, mainly in refugees with PTSD. Alternative and creative therapies such as ‘Arts & Mindfulness Therapy’ or ‘Physical Activity and Exercise Treatment’ have had similar positive outcomes and were found non-inferior to traditional psychotherapies. Group work was highlighted positively in the studies reviewed. Reported benefits included a sense of belonging, peer learning, normalising of emotions and symptoms, and a reduction of social isolation. Most studies included stress-releasing techniques such as meditation and mindfulness practices, stress management, relaxation and grounding techniques and psychoeducation. From this, we can infer that the type of intervention may be secondary, but that other factors are influencing the efficacy of the interventions.

The need for providing practical advice was emphasised by one-third of the studies reviewed. Daily stressors and challenges faced post-migration such as housing, financial difficulties, lack of childcare and transport, asylum proceedings, and acculturation, continue to weigh on people’s minds and hinder their ability to receive support. It is important to value and integrate these stressors and, if possible, address them. This may not be feasible for all providers. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge them and put a specific referral path in place to direct people for support. A certain level of cultural understanding and sensitivity is advisable, if not essential when working with refugee communities and an attempt should be made to gain cultural sensitivity. Communities bring their own strength, experience, and expertise and it is important to value, include, and utilise them. Studies have shown that community engagement has a positive effect on the acceptability of interventions. Creating an open dialogue, providing feedback and being open to learning promotes trust and acceptance. Successful cultural adaption of interventions is only possible if community learning is implemented.

To reduce barriers to engagement, established and accessible safe spaces such as language learning classrooms, community centres, and existing social groups may be used. This has proven to take away the stigma attached to mental health and makes use of existing resources. It further creates an opportunity for socialisation and peer learning and opens opportunities for collaboration with other service providers. The lack of cultural and linguistic capacity was a reoccurring critique among the authors. Language is part of people’s identity and connects them with their roots. It describes the symptoms, emotions, and diagnoses connected to mental health. The language of mental health and the meaning associated with words differs greatly. It is critical to bear this in mind when dealing with refugee populations.

There is a call to move away from a trauma-focused response and focus on the provision of psychosocial supports with a view to promote mental well-being and to prevent mental disorders. Early detection and appropriate support could potentially reduce the need for psychotherapeutic interventions significantly. Facilitating and strengthening resilience in families and communities will have long-term benefits and encourages health and well-being within. “Wellbeing is associated with a sense of resilience and flourishing, rather than just surviving” (Ander et al, 2011). In order to flourish, people need social interactions, meaningful engagements, and purposeful activities. Psychotherapeutic interventions alone, cannot provide this and the social element is equally, if not more important. Admittedly though, pharmaceutical and therapeutic interventions are absolutely critical when dealing with severe mental health problems.

Refugee mental health frameworks or multitier models attempt to incorporate all key points discussed, these models promise to be the most culturally sensitive, sustainable, and effective approach to refugee mental health provision. However, to roll them out on a larger scale requires significant investment, changing attitudes, and a reconfiguration of public policy. Regardless of the intervention or model chosen, several studies demonstrated that the key to effective interventions and acceptability is community engagement and involvement in all parts of the programme. This includes designing the research questions, analysing the findings, communicating the results, delivery of the interventions, and inclusion of training opportunities to build mental health capacity. Building human and social capital by providing opportunities for meaningful occupation, enabling relationship building, and promoting community integration is the most powerful response to refugees’ mental health needs.

It has proven difficult to create a synthesised document for refugee populations as each individual, each community, and each situation requires a different approach. However, while the communities are very diverse, many face the same challenges. Thus, focusing on the similarities rather than the differences might create an adaptable model that diverse communities can identify with. Intervention-based responses, for instance, make common dominators their focal point. Spanhel et al (2019) emphasised the inclusion of:

a) stressors

b) habits, socialisation and values

c) disease treatment concepts

The latter includes cultural taboos and traditional healing methods. Tay et al (2021) identified five domains

1) Safety and Security

2) Attachment and Relationship

3) Access to justice

4) Roles and identity

5) Existential meaning.

They found that the five systems appear to make intuitive sense to survivors of forced displacement. Both studies identified commonalities that apply regardless of background, culture, and religion.

To summarise, significant developments in the area of mental health and psychosocial supports for refugees has taken place in recent years. The studies reviewed in this integrative review suggested a move away from traditional Western developed and led practices. Refugees bring a wealth of knowledge and expertise that needs to be valued and incorporated into modern practice.

Given the rising numbers of refugees, asylum seekers, and displaced individuals worldwide, there is a need for collaboration, information sharing, and joined-up thinking. Refugees’ ability to cope and adapt is largely dependent on the level of support currently provided to them, their social capital, and their ability to access capacity-building services. While we are dealing with individual cases, we need to start focusing on the family, the community, and the environment. Outside the Western model, mental health is not seen in isolation. Therefore, the response must not be isolated, but a holistic one.