Dealing with Anxiety, The Mindful Way

Christine Beekman recently ran a workshop on mindfulness and anxiety as part of Limerick Mental Health Week. Here are some of the key insights for the webinar.

In our increasingly complex world, the intersection of mindfulness and anxiety management has become a crucial area of focus for mental health professionals and individuals alike. While anxiety serves as our body’s natural alarm system, understanding how to manage it through mindfulness can transform our relationship with this fundamental emotion. This guide explores the nature of anxiety, its impact on our lives, and how mindfulness practices can help us maintain emotional balance.

The Dual Nature of Anxiety

Anxiety is not inherently negative—it’s an essential part of our survival mechanism that has evolved over millions of years. At its core, it helps us stay alert in potentially dangerous situations and perform better under pressure. It enables us to make more careful decisions, maintain healthy boundaries, and respond quickly to threats. This protective function of anxiety has been crucial to human survival and continues to play a vital role in our daily lives.

However, it becomes problematic when it exceeds its useful function and begins to control our lives rather than protect them. The distinction between helpful and harmful anxiety often lies in its intensity, duration, and impact on daily functioning. When it starts to interfere with our ability to work, maintain relationships, or enjoy life, it has crossed the threshold from a protective mechanism to a potential disorder.

Understanding the Anxiety Response

Our anxiety response operates through what neuroscientists call the “three-brain” system, a complex interplay of different neural regions that govern our responses to stress and threat. The neocortex, or thinking brain, handles rational thought and problem-solving, enabling us to make logical decisions and process complex information. The limbic system, our feeling brain, processes emotions and memories, triggering emotional responses and influencing behaviour and motivation. Finally, the reptilian brain manages basic survival functions and controls our fight-or-flight response.

When it does strike, we often move from the measured responses of the neocortex to the more primitive reactions of the limbic and reptilian systems. This progression explains why it becomes increasingly difficult to think clearly as anxiety intensifies—our brain is literally shifting from rational thought to survival mode. Understanding this progression is crucial for managing anxiety effectively, as it helps us recognise when we need to take steps to return to a more balanced state.

Common Manifestations of Anxiety

Anxiety manifests in various forms, each with its own unique characteristics and challenges. Social anxiety often presents as an overwhelming fear of public situations, accompanied by excessive self-consciousness and a tendency to avoid social gatherings. Those affected may experience physical symptoms such as sweating, trembling, or rapid heartbeat in social settings.

Specific phobias represent another common form of anxiety, characterised by intense fear of particular objects or situations. Unlike general anxiety, phobias trigger an immediate and often severe anxiety response when confronted with the feared stimulus. While individuals typically recognise that their fear is excessive, this awareness rarely diminishes the intensity of their response.

Test anxiety and performance anxiety affect many individuals, particularly in academic or professional settings. These forms can significantly impact performance by causing cognitive difficulties, physical symptoms, and negative self-talk during evaluations. The pressure to perform well combined with the fear of failure creates particularly challenging forms.

The Two Arrows Principle: A Buddhist Perspective

The concept of the “two arrows” offers a profound framework for understanding and managing anxiety.

- The first arrow represents the initial challenging situation or problem, unavoidable and often beyond our control. This might be a difficult work situation, a health concern, or a personal conflict.

- The second arrow represents our reaction to and worry about the first arrow, the self-inflicted suffering we add through rumination and anxiety.

Understanding this principle helps us recognise where we can exert control. While we may not be able to prevent the first arrow (the situation itself), we can significantly influence our response to it (the second arrow). This insight forms the foundation for many mindfulness-based approaches to anxiety management.

Breaking the Anxiety Cycle Through Mindfulness

Anxiety often perpetuates itself through a self-reinforcing cycle that begins with a triggering event, leads to negative thoughts, generates an emotional response, manifests in physical symptoms, and results in behavioural changes. This cycle can become self-sustaining, with each completion making the next iteration more likely.

The Backpack Method offers one innovative approach to breaking this cycle. Rather than fighting against anxiety or trying to eliminate it entirely, this method encourages us to acknowledge anxiety’s presence while preventing it from dominating our attention. By visualising placing our anxiety in a metaphorical backpack, we can carry it with us while focusing on present activities, checking in periodically without becoming consumed by worry.

Scheduled worry time provides another structured approach to anxiety management. By setting aside specific times for worry—perhaps fifteen minutes daily—we can postpone anxious thoughts to these designated periods. During these times, we can analyze our worries rationally and develop action plans for legitimate concerns while learning to let go of hypothetical worries that serve no productive purpose.

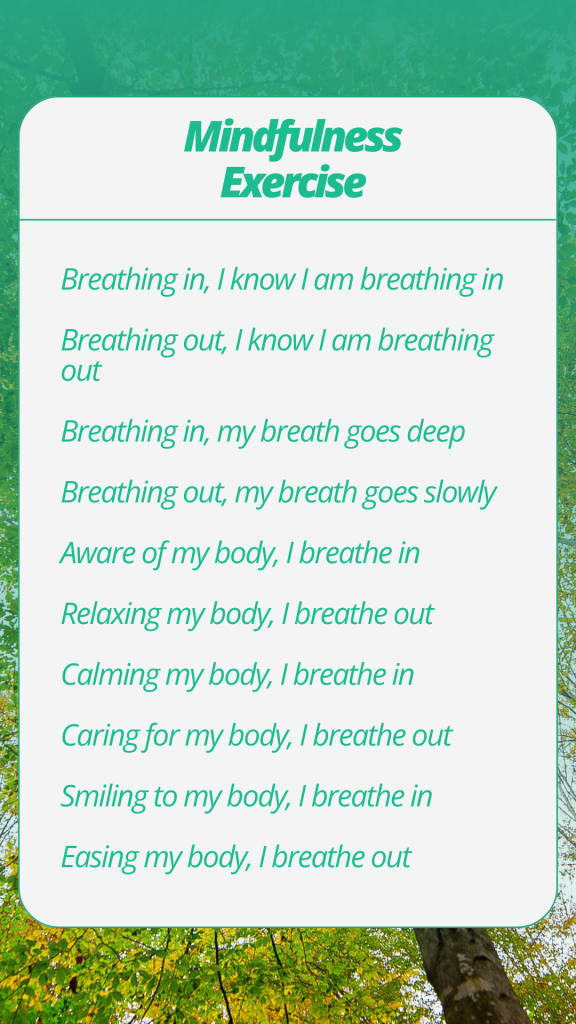

Implementing Mindfulness in Daily Life

Effective management through mindfulness requires consistent practice and integration into daily life. A morning check-in ritual can set a mindful tone for the day, incorporating a brief body scan and attention to breath. Throughout the day, mindful transitions between activities provide opportunities to reset and maintain awareness. An evening review allows for reflection on daily experiences, acknowledgment of challenges, and celebration of successes.

While these self-help techniques provide valuable tools for managing when it strikes, professional support may be beneficial for developing personalised coping strategies, addressing underlying trauma, and learning advanced mindfulness techniques. Mental health professionals can offer guidance tailored to individual needs and circumstances.

Conclusion

Managing anxiety through mindfulness isn’t about eliminating anxiety entirely, it’s about developing a healthier relationship with our anxious thoughts and feelings. By understanding anxiety’s mechanisms and implementing mindful approaches, we can maintain its protective benefits while preventing it from overwhelming our lives. This journey requires patience, practice, and self-compassion, but the resulting emotional balance and psychological flexibility make the effort worthwhile. Remember that progress in management is rarely linear, and small steps forward still represent meaningful change.